If you had been brought up in one of the rising European capitalist economies of the 1700s, how would you have been introduced to the concept of money? There is plenty of material trying to shape values about the all-important ideas of getting and spending, but few have been interested in looking for it. One of the most famous examples, John Newbery’s so-called coach-and-six morality—learn your book, make a fortune trading honestly, and ride in style a gentleman retired from business–has disgusted people with its overt materialism.

If you had been brought up in one of the rising European capitalist economies of the 1700s, how would you have been introduced to the concept of money? There is plenty of material trying to shape values about the all-important ideas of getting and spending, but few have been interested in looking for it. One of the most famous examples, John Newbery’s so-called coach-and-six morality—learn your book, make a fortune trading honestly, and ride in style a gentleman retired from business–has disgusted people with its overt materialism.

That aspirational journey is short on particulars, but it’s a challenge to try and fill in some of the blanks. To make a purchase of sweets or toys, you must know the denominations of coins and their values. Recently I bought a 1755 Dutch primer, Nieuwlyks Uitgevonder A. B. C. Boek, because it includes plates of copper, silver, and gold currency in use there. The antiquarian bookseller remarked that he’d never seen anything like that in a children’s book. The compiler Kornelius de Wit must have considered the ability to identify Dutch coinage as something necessary to be known as with different scripts, and the names of ordinary objects.

I’ve not seen anything comparable in English during the same time period, but that doesn’t mean that filthy lucre is invisible. What does come to mind are pence tables in verse teaching currency conversion, which don’t illustrate the coins with which the children in the illustrations purchase commodities…

I’ve not seen anything comparable in English during the same time period, but that doesn’t mean that filthy lucre is invisible. What does come to mind are pence tables in verse teaching currency conversion, which don’t illustrate the coins with which the children in the illustrations purchase commodities…

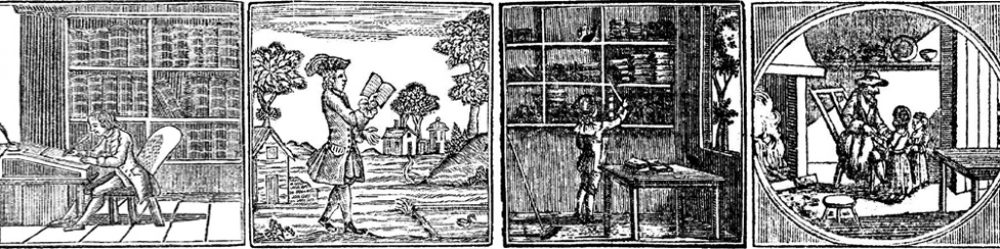

Illustrations of coins do exist in later 18th-century English juveniles published by the Newberys and they are interesting because they reflect overlapping ideas about the idea of wealth. Some, like this one of a miser, caution against the too strong a love of money. He lays up a hoard of money, but being unable to part with it fails to use his riches to benefit the less fortunate or the economy. People receiving windfalls of cash are depicted in two other illustrations I’ve found. The frontispiece of Richard Johnson’s The Foundling; or The History of Lucius Stanhope (1787) shows Fortune scattering a shower of money down on the heads of the people around her. Down on the ground is a fool in a cap with bells on his knees trying to scoop up whatever he can. It’s very much in the story’s spirit, which shows an heir to a fortune squandering it, s sharp contrast to his adopted brother of low birth, who makes a fortune and preserves it.

People receiving windfalls of cash are depicted in two other illustrations I’ve found. The frontispiece of Richard Johnson’s The Foundling; or The History of Lucius Stanhope (1787) shows Fortune scattering a shower of money down on the heads of the people around her. Down on the ground is a fool in a cap with bells on his knees trying to scoop up whatever he can. It’s very much in the story’s spirit, which shows an heir to a fortune squandering it, s sharp contrast to his adopted brother of low birth, who makes a fortune and preserves it.

The other is difficult to interpret without having read “A remarkable Story of a Father’s Extraordinary Care and Contrivance to reclaim an extravagant Son” reprinted in A Pretty Book for Children from the 1701 5th edition of Giovanni Paolo Marana’s runaway best-seller, Letters from a Turkish Spy. A young man has run through all of his estate except for the ancestral home, which his father urged him to preserve in the family. The desparate son goes to the room where his father died to hang himself. He runs the rope through an iron ring in the ceiling and when he jumps, the weight of his body pulls open a trapdoor, out of which spills a shower of gold which his father hid there to save him from himself. Grateful for his father’s foresight (and knowledge into his character), he reforms and buys back the estate he lost.

Notice how the coins here and in the block of the miser are drawn with crosses across their faces. I assumed it was a widespread representational convention, but I showed them to Alan Stahl, our curator of numismatics, he said he hadn’t seen anything like this before.

In the coming weeks, look for a post on supply chains in children’s books…